Decoding Wine Labels: How to Know What's Inside the Bottle

Wine labels can tell you far more about what’s in the bottle than just what meets the eye. However, knowing a few simple decoding hacks is key. Here at Verve Wine, we’re all about ensuring that you get exactly what you’re looking for when it comes to choosing top-notch bottles -- and knowing how to decipher what’s written on the label (both front and back!) is a great place to start.

When breaking down wine labels, the first thing to know is that Old World and New World wines are labeled a bit differently. The main difference here is that Old World wines (Europe) are labeled by their region/appellation, while New World wines (North America, South America, New Zealand, Australia, etc.) are generally ticketed by grape variety.

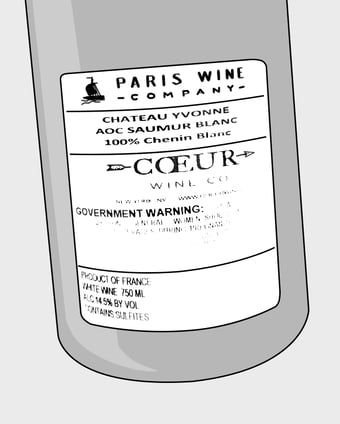

Check out these two bottles of Chenin Blanc, for example (below). Château Yvonne (Old World) labels their wine as Saumur Blanc, while Lieu Dit (New World) writes Chenin Blanc on the label. So why the appellation over the grape variety? There are many debates as to why this is, though a common theory is that Old World regions tend to be a bit more knowledgeable on appellations and varieties given their winemaking histories and culture around drinking wine. Therefore, adding a ‘Chenin Blanc’ labelling under a Saumur Blanc designation would be slightly redundant.

Another example of this would be a Napa-based producer identifying their wine as a Cabernet Sauvignon or Merlot, whereas a Bordeaux producer would label the bottle by its appellation (think Haut-Médoc for a Cab-dominant blend or Saint-Emilion for a Merlot-dominant blend). In Australia, Syrah/Shiraz-based wines are generally identified as such, while a Northern Rhône red would be identified by its appellation: Cornas, Crozes-Hermitage, and so on, as identifying these wines as Syrah is deemed obvious.

Aside from this monumental difference, labelings tend to look relatively similar. Here's a breakdown of what you’ll find on most Old World/New World bottlings:

Old World

Old World wines will always have the name of the estate (here, Château Yvonne) prominently visible on the label, followed by the appellation (Saumur Blanc) from which it comes. The appellation designation is generally labeled right below. This wine is from Saumur Blanc, so the designation here is ‘Appellation d’Origine Controlée.’ IGP wines will be labeled as such, or written out in full as Indication Géographique Protégée, and Vin de France wines will either have ‘Vin de France’ or VdF somewhere on the label.

📸: Verve Wine

📸: Verve Wine

Old World wines always state where the wine was made (Mise en Bouteille, in the case of French wine), the vintage in which the grapes were picked (2018), the alcohol percentage (13.5% ABV here), and the size of the bottle (750 ML) on the label.

📸: Verve Wine

📸: Verve Wine

But wait! The information doesn’t stop there. There’s a whole lot to be learned from a wine’s back label, too. Aside from potential producer information and tasting notes (these are optional), the back label of a foreign wine is always required to state who imports it into the USA. This hugely important piece of information could be key in finding new wines that you’ll love!

Perhaps you’ve noticed that the last two bottles of wine you’ve really enjoyed both came from Coeur Wine Co, Louis Dressner, or Grand Cru Selections. Chances are that your palate highly identifies with those of the wine buyers at said importing company, so when venturing into the world of new wines, there’s a good chance you’ll seriously enjoy other selections from their portfolio, too.

In addition to the information above, back labels of Old World wines will always depict a Government Warning on alcohol consumption, a statement of what the product is (here, White Wine) and where it’s from (Product of France), as well as the ABV and a sulfites notice if applicable.

New World

New World wine labels are slightly different. Like Old World wines, you’ll see that the producer (Lieu Dit) is prominent on the front label, as is the appellation where the wine is made (Santa Ynez Valley).

%20with%20vintage.jpg?width=340&name=lieu%20dit%20front%20(BW)%20with%20vintage.jpg) 📸: Verve Wine

📸: Verve Wine

However, unlike Old World bottles, the grape variety here is explicitly written front and center. The wine’s vintage is also evident on the front label, as is the ABV (though at times this may be relegated to the back label).

.jpg?width=341&name=lieu%20dit%20back%20(BW).jpg) 📸: Verve Wine

📸: Verve Wine

Similar to Old World wines, New World back labels will also reiterate where and by whom the wine was produced, a government warning, and a sulfites message if necessary. An exception to many of these rules, both for Old World wines and New World wines, is the labelling of natural wines.

Many natural wines will simply depict a quirky design or image as a front label and leave all required information to the back label. The back label will always be required to state the producer, where the wine was made, a government warning, importer information, and ABV percentage, though the rest is optional. Many natural wines do not contain added sulfites, so this message will not be present, and a good handful of the wines do not add producer details or tasting notes.

📸: @lasjaraswines

📸: @lasjaraswines

Another labelling detail to break down is the use of organic and biodynamic mentions. It’s imperative to know that organic has a different definition between Old World and New World (USA) wines. Old World wines can be deemed ‘organic wines’ if they are made from organically grown fruit. However, such is not the case in the United States. American wines must not contain added sulfites to be dubbed an ‘organic wine,’ though if the wine is made with organically farmed fruit, the wine may state ‘Made with Organic Grapes’ on the label. With regards to biodynamics, if a winery works with Demeter certified vineyard sites, the label is permitted to boast the Demeter logo.

However, the most important takeaway here is that most wineries that farm organically/biodynamically choose not to become certified and/or do not add the certification logos to their bottles. Why? A handful of reasons. Certifications can be extremely expensive and most small family wineries simply can’t afford them. Others choose to opt out of organized constraints and simply farm in ways that they believe to be the most respectful to the environment without an overarching board of rules governing their techniques.

The best way to find out if a wine is organic/biodynamic, as well as other information regarding producer, vintage, and tasting notes? Find a shop that you trust and count on the reliable staff to provide you with all of the additional information you need! As handy as it is to know how to read a wine label, a well-versed team member will generally always have more insightful (and interesting!) information to share.